Lucy Shelton is one of the great American sopranos of the 20th and 21st centuries Lucy, the only two-time Naumberg Competition winner, has gone of to have an illustrious performing and recording career. On December 15, 7 PM at National Sawdust (80 N 6th St, Brooklyn), Lucy will present a “Tasting Menu” of her favorite works, including music by Stravinsky, Cage, Carter, Crawford, and Ran. On this podcast Chris interviews Lucy about her life, her career, and her advice for young musicians and singers.

This House, Those Dreams

A project of late is to order memories, secure them, put them in some sort of firm chronology, and yes, write about them.I will admit to a sort of low grade middle aged crisis with this, in that I have been mostly complacent and in a blur for a few years now, but the sudden acceleration of mortality of those around me has shaken me from the stupor, and I realize that many things I used to have at easy command in my memory bank are slipping away.A few years ago, while co-chairing one of the largest music conferences in the country, people working closely with me commented on my “mind like a steel trap” as I had the entire map of hundreds of events, all the costs, all the details, right there for instant access. Names, amounts, sizes of each room, each stage, all there.In the personal realm, it was much the same.Everything was still new, still fresh- every detail of school life, every detail of growing up, everything about getting married, down to the level of where everyone sat and what everyone said.I had it all in the steel trap.

That trap eroded, and I am not sure when, or why, or how, but here we are. It is now a leaky sieve that things go in- a few things stick, other things leak.

I call it, for lack of better term, the fours. In our youngest days, we care about what happens in four minutes. Then we grow older, and what happens in four days starts to matter, then four years, and so on- you get the picture. The last in this list is important in that four years of college provide so much fodder for memories that are vivid- right at that stage when your frontal cortex is starting to really gel, well, that is right when you fall in love the first time, right when you can procreate for the first time, right when you learn to dismiss authority, in short, right when life really matters, that is when everything is a beautiful Technicolor, and you relish this wonderful reality and cling to every last thing. And remember every last thing. Those of you around my age who engage almost daily with your college friends on Facebook know exactly what I mean.

But as life sweeps along, days get longer, periods of time stretch out, and the blur sets in. If you are not careful, you wake up one day and realize that 3-5 years have passed, especially when you see something as simple as an unreached goal, e.g. I will paint that window frame as it is chipping, some day. And that day keeps slipping. And then that unpainted window is a sudden, jarring reminder of the passage of time and an existential crisis that hits you as you herd your kids out the back door for school and you haven’t had coffee yet.

Suddenly you find yourself in a state of suspended time where everything returns to Technicolor. You are sitting in a quiet hospice room with a loved one, looking out at the bird feeder and you see every movement of every bird, and each moment sears itself into your memory. You read an email about a colleague, released due to budget cuts. You see your son limping after a simple ankle twist on the playground and your life, your vision, all focuses with preternatural hyper reality. And in those moments you also see the past in sharper focus, and you want everything to be aligned in perfect order, and you panic, maybe a lot, when the alignment is not as clear, when the moments are going away, or quite simply, gone.

What does that have to do with this photo? Almost a year ago now, I visited the small PA town of my youth. As I was taking pictures of the house where my family lived for many years, I gravitated to this porch. One memory persistently called to me, and I wondered if by looking at that space, if I would regain something I lost. Spoiler alert: I did not. On this porch, we had an old and beat up piece of furniture we referred to as a “davenport”. I wanted to reengage with this spot as I thought it might carry some sort of spiritual or at least deeply personal significance in that when I was 14 or so, I found a copy of The Catcher in the Rye on a bookshelf in my oldest brother’s room, and for some reason, I picked it up, went out on that porch and sat down on that davenport, and for the first time in my life, I read an entire book in one sitting. Incidentally, I know that the second book I read in one sitting was Bronstein’s Children by Jurek Becker, and I know the exact spot- the middle of the soccer field at Interlochen- where I sat on a Thursday afternoon and read it without pause. I remember the class, the teacher, the essay I wrote about the book, the questions about it I stayed after class to ask the teacher, etc. It is all vivid. I remember asking my parents to find me more books by that author in the pre internet days, and their efforts to track some down by driving to bookstores a couple hours away to ask in person if they knew of any, and the constant search in bookstores in NYC, Ann Arbor, and other spots when I was roaming about in college. I miss those days when an author and a book could be a mystery that took years to unpack. Google has taken away a certain amount of magic in our lives.

Anyway, I thought that if I stood near that porch and stared at it, I would suddenly be in touch with that 14 year old boy who fell down a well the first time he read Salinger and has struggled ever since to climb out. I did not. I also remembered the little boy who stood at the screen door at one of these doors when lightening hit nearby, and how he jumped and ran, scared out of his mind. (that same boy has been within 500 feet of lightening strikes three times in life, but I digress) I remembered my grandfather sitting on that porch smoking a pipe before dinner, and the brand of tobacco he used from a store in New Haven, CT, and only there as he was a man of habits, something that I now can claim for good or ill- (Owl Tobacco, and I can still see the orange and white canister it was stored in, sitting on a shelf in the butler’s pantry of that house) and so on.

I want to order memory, but it is a cloud we cannot grasp in our hands, a shifting world that will come to us in fragments, and in dreams.

And only in dreams.

So where are you from?

I am not one for small talk. Weather is only moderately interesting, local politics

will always be the same, I do not watch TV, nobody will ever be happy with local

snow removal, gas prices suck, and while I care a little about the local sports team as

a fun diversion, I have no firmly held opinions about their future success. Most of

what we call civilized talk is a shadow puppet display that simply says, “I will

pretend nominal interest in you” while we try to move on to the next, or worse still,

the only things we have to say to each other are patently pathetic as we do not have

much else of merit or interest to say. Sometimes the shit-eating grin and manly

handshake is sincere, and that is even more frightening.

Put two people in close proximity in airplane seats and small talk seems to be

implied. If one of these happens to be a wannabe alpha male seated in business or

first class, a world that has been thrust on me simply because 1) I am huge and no

longer fit in regular airline seats and 2) my career has calmed down to a point I do

not fly much, so when I do, I can afford, some of the time, a fancy seat, well, then I

am stuck making small talk.

So imagine the corporate VP, the real estate investor, the shower curtain ring

salesman with an absurd amount of skymiles, the stereotype of the alpha who thinks

he belongs there, thinks he is something special (yes, always a male) and thinks that

he has something to prove. Imagine he sits next to me, and the opening salvo is “So

what do you do?”

I’m a flute professor.

I know better now than to say that. I usually put forth a fart cloud of obfuscation. If

my “don’t talk to me, I’m tired” vibe is not clear, I try to bob and weave and say

things about “non profit consulting” or another false path. It usually works.

But then the question about “where are you from” floats to the surface. Suddenly it’s

not an uncomfortable couple hours on a plane, it’s like every small talk effort at

every party, ever- from the getting to know you awkward college world to the even

more ridiculous world of adult cocktail parties decades later. It is a question I

despise.

Where am I from?

It’s complicated.

The simple answer is Yellow Springs, Ohio. I have lived here since 2006. Before

that, I lived in Cincinnati, Ohio. I never imagined this would happen, but I have lived

most of my adult life in Ohio, and have lived here more than anywhere else.

But the question usually probes into your childhood. But -where are you FROM.

Where did you grow up? What is the formative world that launched you into the

present?

In the present, most people assume I am from Michigan somehow. I live there in the

summer, my father lives there, and I suppose I pass as someone who could be from

Michigan, and my four years of boarding school in northern Michigan sort of seal the

deal. I don’t have any discernable accent, but I do slip into an “eh” at the end of a

sentence once in awhile, and the word “car” does come out of my nose on occasion,

so I could be from Michigan.

I usually allow for the water to be muddied like this. And when I was younger, I

made it even worse. People would ask, and I would intentionally mislead. I would

try to avoid the obvious. I was from New York, Michigan, or any number of places.

Just not the truth. Honesdale, Pennsylvania. The place I moved to when I was in

kindergarten. A place that I tried, for various reasons, to leave as soon as possible.

A place I did leave for high school and beyond. The home that I had as a kid, a place

that remains in my memory as home, yet a place that makes me mad, sort of happy,

sort of sad, and everything else all at once.

A place that I can still remember. A place where adults praised and tormented me in

equal amounts. A place where I was a preachers kid. A talented kid. Maybe a

troubled kid. A pressure cooker, in other words. A place where kids on the bus spit

on me. A place where I wanted to play baseball, but was so inept I was first cut from

a team and then sat on the bench, and where practices were an ongoing torment of

other kids teasing, bullying, and otherwise being terrible. The son of a local lawyer,

not incidentally, a member of my father’s church, who teased me every time I was

up for batting practice, saying I looked “constipated” in my stance.

The place I am from is real. Wonderful, and terrible all at once. There are

wonderful memories. But they are eclipsed by the rest.

I went back in 2005 when my father retired. That is an essay in itself. Then I went

back with my family in 2017. There is no revelation, no truth, no epiphany in these

visits. A look down a big black hole, and a bit of anger certainly.

What you see in the picture is the church. For 150 or so years, a mainline

Presbyterian church. Flawed, certainly, but familiar. Trained theologians at the

helm. In the last decade, it has been radicalized and turned into an evangelical

stronghold. Nary a seminarian, at least in the traditional sense, in sight. The past is

obliterated to make room for the radical, and yes, the stupid and mindless.

There is a beautiful contradiction in life. Here is one- Classical music is dead,

long live Classical music. Another- burn it all down, let it live again.

I have a lot more to say about where I am from. About clergy abuse. About bullying.

About the joy and agony of small towns.

I am a preachers kid from Honesdale, PA. That is where I am from. That is who I

am.

There is more to come here.

Random Thought on Abundance

Three Botticelli pictures, my favorite Respighi piece, one that I have always loved,

was on the radio earlier tonight. Yes, I listen to classical public radio, but streaming-

thru my Sonos stereo speakers in my living room.

So, as I almost always do, I stopped what I was doing (dishes) and sat down and

listened in quiet rapture.

But as I listened, this thought occurred to me- why is this suddenly a special

occasion? With these same speakers, I can instantly open my iPad or iPhone and

dial up the player, and access AppleMusic, Spotify, the Naxos library, and a couple

other streaming libraries with thousands of recordings. If I really want to hear the

piece, I can push a couple buttons and have it blasting all over the house whenever I

want, in good quality sound. (As long as the power does not go out, a threat made

very real by our crumbling infrastructure and inability to fend off hackers, etc. But I

digress. Everything is fine; let’s just move on. Or something.)

And if suddenly I need some new socks? Open up a device, do some clicking, and 2

days later, there is a package on my doorstep.

So basically, anything you think of, as long as you live in the world of privilege as

many of us do, you can have it. Quickly. It’s magical.

As far as music goes, I remember the giddy delight of finding a CD (or cassette or LP)

in a record store- one that I wanted, but could not easily find. I distinctly remember

when the new Borders store opened in Rochester, right around my college

graduation, and my parents took me there and offered to buy me whatever CD I

wanted. It was a big, full new store, with more CDs on display than my feeble brain

could process. I found the Nagano recording of Poulenc Dialogue of the Carmelites

that I loved and so desperately wanted, and I’m quite sure I danced a little jig out of

sheer joy. There it was! Something I liked, and had been looking for, and I could get

it. Right then. Amazing.

For that matter, put 20 year old me in Tower Records in NYC with about 30 bucks in

his wallet, and imagine the hell of trying to narrow down the choices of what to buy.

Imagine the amazement – so many great recordings, so much music, so many

choices. What we have now at our fingertips was a once in a blue moon, if that,

type experience just two decades ago.

In the blink of an eye, we are drowning in information. I know this is not a new

concept, but I wonder if we have stopped long enough to really think about the

consequences. And I wonder if we are raising kids in this world of absurd

abundance with no concept of how dazzling this really is, and what unknown worlds of harm could be the result? Not the least of these, as we see with the ever-growing

threat of disasters, both from nature (fires, for one) and from idiots (politicians of all

parties, for another), do we have ANY concept of impermanence, or will we just let

life ending disasters occur while we play candy crush and roll our eyes? Do we

have a concept of working for something? Of real enjoyment? If we just consume

and discard and move on, brief in our connections and our desires, what will we

become?

No conclusions, only questions. And if you don’t know the Respighi, go listen. It’s a

marvel.

Anxiety or Honesty? Both.

It is odd how certain topics bubble to the surface in the sea of noise on Facebook, at least within my own relatively small and somewhat skewed sample of associates. (Read: tons of musicians, teachers, artists, freethinkers, and some others).

Also, it is odd how much people care about these topics for a day or so. There is a lively, maybe heated exchange of comments, and then it fades. Back to cat pictures, polemic political rants, cute photos of your kids, some slightly blurry food pictures, then a new topic emerges. Repeat.

A recent example: tons of posts and reposts of articles about Anxiety in college students, and how it appears to be worse than ever. How they can’t take criticism without breaking. Lots of hand wringing, pearl clutching, grandiose statements, mild arguments, gross generalizations, and “kids today” type statements are bandied about, and then it’s the next day and nobody seems to be talking about it.

I for one do not want to give up on this topic. I have a unique perspective in that I teach private flute lessons, one on one, so my contact with my students is far more intense than a “typical” college professor. And, in the Arts, we are often dealing with the depths of someone’s very being when we are dealing with what we do; so “intense” is an understatement at best.

Case in point: yesterday, I had a frank conversation with a student about a recent performance, and it resulted in an emotional, tear-filled reaction. The general flow of it was this:

ME: What do you think about your performance last night?

Student: I thought I did great, and there were some moments I really went for it musically and it felt pretty good, and I didn’t miss that many notes, so it was OK.

ME: Yes, but…your intonation was terrible, you missed far more technical details than you realize, all of your releases were not good, you did not balance on your feet the way we have worked on, your tempos were way too fast, your dynamic range was, as we have discussed, not at all interesting as you simply cannot play loud all the time, (insert a few more points here) and overall, you kind of brutalized a great piece of music while reverting to a lot of really bad habits that we have spent a semester trying to undo. I expect a lot more from you, and we have a long way to go, so get ready to work even harder.

Student: wilts, tries to keep composure, cries

I know at this point many of you will stop reading and say “well, you are just an asshole” while some of you will cheer for me as some sort of Gordon Ramsey like soothsayer, but look, it’s not an uncommon moment in the development of a student, in this case, a graduate student majoring in flute performance.

What does this have to do with anxiety? Well, a great deal of what I am reading about anxiety in teen and college students dwells on the idea that they simply cannot take the level of criticism it requires to really learn. Granted, there is more than a little truth to Branford Marsalis’ viral youtube rant about how students today are more interested in saying they are doing something and being told they are great for doing it instead of really investing the time and really hard work to actually do it- but I wonder if dismissing ALL students like this overlooks an important point: there are more students than we realize who are not coddled, and yes, not so anxious they can’t function without falling apart when the slightest bit of conflict or truth comes their way.

Maybe some of them are raised to be emotionally honest and not hide their feelings.

And maybe my student was used to getting away with a glib dismissal of their mistakes to cover as we all do, but when that was pushed aside and I pushed deeper, the reality of the situation was clear and they felt bad. Really bad. Tears, bad feelings, deep breath, time to pick it up and keep trying. And try harder.

That has nothing to do with Anxiety. I think a lot of what we label as “kids are so anxious” is simply kids being emotionally honest. Because they are raised that way.

And I for one think that is for the best.

I think back to moments in my own development, and I think of some of the ways my teachers/mentors talked to me. If I am honest, I can think of many occasions, some profound and life changing, some just every day, where people talked to me in far more brutal terms than those I use today. Hell, I once had a conductor call me a “fucking idiot” in a rehearsal. Oh, and he called me the exact same thing in conducting class a few weeks later, kicked me out of the class, and said I needed to go back to my dorm room and study the score one note at a time because I was “too stupid” to understand it.

I broke in private in those moments. But I never broke in front of the teachers. “My generation,” using that term loosely, was not taught to be emotionally honest. Especially the males of the species. Previous generations had it even worse. Gone are the days of ruler-wielding piano teachers, tyrannical conductors (mostly gone) and the like, but everyone over 40, before you cast aspersions on your young students, think back to your training and your experience. Were you emotionally honest? If someone tore you the proverbial new one, did you react? Of course you grew from it, but what if you said what you really felt in the heat of that moment, got it out of your system, and did not dwell on it after that?

There are coddled students today for sure. But there are tough students today as well. Before you simply dismiss everyone half your age or younger as “anxious” or “soft,” take a minute to look back on your own education and think about it.

You probably should have cried a lot back in those days, but you did not realize it was ok. Don’t discount the strength of your students for doing so.

Be Nice

There it is, right in the title: my main piece of professional advice. Be nice. Now, the notion that I'M the one giving this advice is laughable for those who went to school with me or knew me early in my professional career, because "being nice" was never very high on my agenda. But having spent a couple of decades in the music business - as a tenured professor, an orchestral player, a chamber musician, and now a producer/performer in New York City - take my advice and let me have taken a few hits you don't need to take: be nice.

When I was a senior at Indiana in 1993, a freelance musician from New York came and spoke to the senior class about the reality of making a living as a musician (I wish I could recall who that was, but I don't). She gave us copies of this book, "Making Music in Looking Glass Land", which is about the details of being a working musician - press kits, headshots, resumes, and many other details. She also gave us this advice: be nice.

Well, all of that might as well have come from Mars.

First of all, every major school of music in the early 90s was holding on to a very old model of professional development. Almost all of my own training was pointed toward one direction: getting a job in an orchestra. So professional development basically consisted of "here's how you take an audition, now good luck to you". That was basically it. So when this person arrived with the news that there was so much more to being a working musician that I had ever even imagined, it came as a real shock to my system. I thought you just won a job and then you were set. It blew my mind and, frankly, intimidated the shit out of me.

And then there was the nice thing.

22-year-old me (really just an exposed id at that point) was like, "get the fuck outta here with that shit. If I come in there and kick ass, that's how I'll win a job. It doesn't matter if you smile if you can nail everything!"

Guess what? It matters.

It matters even more than ever, actually. The level is very high out there, and only getting better. At any level of job, from major principal auditions through adjunct professorships to regional sublists, the likelihood is that there are at least 20 people who could do the job as well as each other. In many situations you're talking about a multi-year commitment, not to speak of tenured jobs, where you're likely to work with the same people for a decade or more. The simple truth is, no one wants to work with an asshole. And in today's environment, one doesn't have to. Showing up on time with positive energy goes a very long way, especially in a field so full of daily pressures, travel, and such. That's not to say you can't be sarcastic, acerbic, or the like. In fact, those are net positives. Just be like The Fonz, and be cool. You want to give them every reason to call you back.

More than that, being nice is just a better way to move through the world. Again, this has not been my main mode of being my entire life. In fact, I would say that for the first 40 years or so of my life, I was a miserable prick. I remember one bit of advice I got from Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr, who was my teacher during my doctoral work. I could be fairly volatile at the time, and I must have displayed my temper or some such, and she took me into her office. Quite gently, and really without judgement (she is wise), she said, "you know, Chris, what you really want to do is to make people's days better when they see you. You don't want to make someone's day worse for having run into you". She was, of course, right. And I did hear it, though it took me some time to be able to be that person. Therapy helped.

Be good to each other. Be kind and generous to your fellow musicians and friends. There's my professional advice.

Supermarket Trip

Today on the way home, I impulsively stopped at the new grocery store- you know,

the one built right next to the old one, but twice the size. It’s surreal to begin with

just looking at the old store, which I always thought was more than sufficient, yet to

be torn down, already showing signs of decay, while right next door is a massive

new structure.

Stores like this tend to make my head spin. If you take just a minute to think about

the abundance on display, and what it really means to go from one massive aisle to

the next and see all the products (the SKUs, in retail parlance) on display, you can’t

help but think that the world is equal parts amazing and pushing into levels of

sickening consumption unparalleled in human history. Salmon from Chile, soybeans

from Vietnam, avocado from Mexico, canned goods from god knows where, piles of

cheaply made non-comestibles like plates and glassware, all made in massive

factories overseas, and so on. All of that plus hundreds of thousands of more things,

all there for the taking. And here is the kicker- the same corporation also operates a

store just like it, less than ten miles away! And another ten miles west of that! On and

on, endless consumption, anything and everything you want, all at your doorstep or

pretty darn close. It was pushing 90 degrees outside but people working in the store

were wearing sweaters because the AC was so strong. Tell me how THAT is a

sustainable use of electricity. Again, think about that replicated several times over

in every direction. It is a massive undertaking to be sure, sadly impermanent as we

see when nature throws storms and other such at us, an accomplishment of moving

materials like food across vast distances, but ultimately a testament to our callous

disregard for the world we inhabit.

These are the thoughts rolling thru my head as I walked in the door. But then it hit

me. This is the reality we have created. This is the privilege we make available – to

some, not to all- that past generations have fought for. This is the freedom we

gained, of a sort- not to tell people the proper way to respect artificial and

problematic symbols of patriotism, but to live in a world of abundance, free

from want. So how is it that some people living in this comfortable world, where

they are literally consuming themselves to death, can go home from this

exaggerated beast of a grocery wonderland and sit down and think, “our country is

not great?” And how is it that some of those same people are so blind to all those

who see the abundance and ask, “what bootstraps can I grab to get some of that

when all I see are barriers?”

So I guess I will stick to my family run grocery store in walking distance from my

house, where I know the owner by name, and where they might have far less to offer

but I can still find more than I will ever really need.

On Writing. On Silence.

In spring of 2002, as I was crashing and burning in a job that did not suit me, and as

I wrestled with the ramifications of that tailspin – I was employed at one of the best

music schools in the world, I was making my mark in a way that attracted attention,

I had mentors, serious mofos in the business, telling me that if I could stick to it for

20 years or so, I could claim any top job I wanted at a major American music school,

and despite the future I could clearly see, the clear path in front of me, I was not

happy.

While I thought about leaving, I had a vision. The job I had required nearly non-stop

talking to people, and what I saw, on more than one occasion, was a day where I was

sitting quietly, with nothing to say. I saw hours of silence, I saw myself surrounded

by people but disengaged, quiet, and I felt a silence brewing within that I could not

name or describe- a point where there were no more words coming from me, a

point where nothing sounded right, a point where I simply sat still, silent.

I thought when I left the job in May 2002 that I would lapse into that silence. I did

not. True, I fell into a major depression that lasted for months, perhaps a year, and

there were many days I did not leave our apartment. But I was full of words. They

were all ready to come out. And come out they did, once the stars re-aligned and I

had the chance to talk, and write again. From Fall 2004 on, I was a non-stop babble

machine. Hundreds of essays in American Record Guide, DPO program notes, hours

and hours of lectures both at school and in public, papers, thoughts, basically,

constant energy. Once unleashed, I did not stop.

Even when I slowed down, I still cranked out blog posts here on Open G. Notes,

ideas, thoughts, letters, and in the classroom and studio, hours and hours of talking.

If you know me, you know I don’t engage in brevity. An hour lesson block is barely

enough to cover everything. Hell, even my Facebook posts push the 500 word mark

a lot.

But that silence I saw back in 2002? It has finally crept in. I can go for days where I

have little, if anything to say. I sit down to write, and I can only stare. I wish I had

an explanation, e.g. I have worn myself out, or I finally realized I have little of value

to add, or something profound. But I can’t say that. I still crave the 500 word essay

spilling effortlessly from my fingers with Mozartian grace. I crave the attention, the

accolades, the feedback. But there is nothing.

So I propose that it is time to re-launch my blog presence. I need to explain the silence. I need to push back against it. I need the babble. I can revel in the quiet as it makes me happy at times, but I can’t be quiet for good, especially as the world pushes to new levels of precarious balance, as all I hold dear is under threat, and on a personal level, as I continue to struggle with the deaths of family and close friends. Maybe I have been saving up a howl at the moon. Maybe my vision of quiet was the worse case scenario- a vision of where I could be if I gave up.

I’m not going to do that yet.

Peace.

Chris Chaffee is a flutist, a professor at Wright State University, and Vice President of Keepin' It Real for Open G Records

Zero to Sixty: The Short Camp

In this previous blog, I compared the way I prepare for performances to a boxer's training camp. Well, this time I have something a little different: a short camp.

In late January I went to the doctor with pain in my side. Turns out I had three significant kidney stones - one on my left side and two in my right. This means I had to undergo two consecutive surgeries to correct them, which means it's been about two and a half months since I last played my horn.

I have a performance next Friday night.

Can I beg out? Sure. I even have my replacement lined up (the supremely talented Mark Dover), but I really want to do this one. Actually, I really only need to do one piece, but even that is a tall order to do in front of an audience when you've been off the horn for so long. I'm also determined to play this piece (more on that later).

So how am I going to get to speed in just over a week? Once again, I think of boxing: sometimes fighters will take on bouts with very short notice - someone gets injured, gets popped for drugs, any number of reasons. It only works if you were in good shape to start out with. You can't come from LESS than zero. So I'm going to lean on my go-to routine, the method. This means lots and lots of fundamentals - getting back to the roots. I will take the method and expand it over five days until I'm as close to 100% as I possibly can get. The first day I will barely play an hour. By day five, I should be ready to play a full three hour rehearsal. How? I will literally show you.

Tune in to Open G Records' YouTube channel, where I will be sweating and suffering live for both my and your benefit.

So now let me tell you why I'm motivated to torture myself to get into quick shape. This piece, Moonset No. 2 for soprano and clarinet, is by my dear friend David Glaser. The first time I performed it was also the first time I met David. I played his piece at East Carolina University with a soprano who just murdered the piece, and I don't mean in a good way. David had come down from New York to hear the performance, and I was so fucking angry and embarrassed. Here I was, in North Carolina, trying my hardest to be great and then giving a shitty performance in front of a New York guy. It was almost unbearable. It was also clearly not my fault - normally I take it for the team, but this was really egregious. After the performance, I apologized to David and I said, "listen, man. Write something for me and I'll make sure it gets done right". Well, he took me seriously, and a couple of years later I premiered his clarinet concerto, the first concerto anyone ever wrote for me. This will be my first opportunity to play the David's Moonset since that fateful Carolina day, and that's why I'm so determined to be able to do it. I do love a challenge - it's a bit like "Fuck me? Hey, fuck YOU!"

Open G Podcast #11: Harold Meltzer (Part one)

Open G Podcast #10: John Harbison

In this episode, Chris interviews noted American composer John Harbison. In this wide-ranging, almost two hour interview, Harbison talks about his music, his work, and his life, including his time in Jackson, MS in 1964 as part of the Civil Rights struggle. Check out an incredible concert of Harbison's piano music, January 25 at National Sawdust. More info here.

The Method, Part One: Longtones and warmups

We've all heard people do freakish things behind practice room doors. The thing is, I never see those players make the finals of high-level auditions. I call them "practice room heroes". Don't be them. You want to build practical, even, reliable technique that will allow you to play even the most difficult music with musicality and fluidity. Plus, showing off is for suckers.

The Method or: What The Hell Am I Doing?

Open Podcast #9: Christopher Stark

Chris talks to Christopher Stark about growing up in Montana, his unusual path to musical success, and his relationship with his mentor, Steve Stucky.

Be sure to like and subscribe to our podcast on iTunes. Search for Open G Records!

Notes for Steve

Here we share our program notes from last night's Steven Stucky celebration. Thank you, Jeremy Gill, for your incredibly moving and beautiful words.

IN CELEBRATION OF STEVEN STUCKY

“One kind of artist is always striving to annihilate the past, to make the world anew in each new work, and so to triumph over the dead weight of routine. I am the other kind. I am the kind who only sees his way forward by standing on the shoulders of those who have cleared the path ahead.” — Steven Stucky

Tonight we celebrate the life and music of Steven Stucky in a program that comprises music by Stucky, some of the composers he loved and admired most—on whose shoulders he proudly, unrepentantly stood—and a few of the myriad younger composers he championed and guided.

Itʼs impossible not to hear the deep and manifold connections that bind the works on tonightʼs program together, which form an uninterrupted stream of artistic creativity from Brahms through today. The cascading thirds of Brahmsʼs Op. 119, No. 1 tonight can be heard as foreshadowing the “tall tertian chords” Stucky so lovingly documented in his early study of Lutosławskiʼs music, and that permeate the fast sections of his own Sonata for Piano that closes tonightʼs program.

“Sereno, luminoso” from Stuckyʼs Album Leaves (written for and dedicated to tonightʼs pianist, Xak Bjerken), is a masterful miniature: seven (or is it eight?) phrases that can be heard as first, shortening, then broadly expanding,then reprising (a fifth higher); or, as a simple expansion of register from the center to middle-outer registers of thepiano, pulling expressively against the only dynamic indication in the movement: piano sempre ed intimo.Throughout the texture is homophonic but densely chromatic, mixing the texture of chorale and the resonance of distant bells.

Clanging bells announce Christopher Starkʼs in memory, composed for tonightʼs concert. Stark memorializes his teacher in the time-honored tradition, by converting S(teven) E(dward) S(tucky) into the pitches E-flat–E–E-flat, which sound, first hammered in the lowest register of the piano, and then, after a restless, harmonically cyclical interlude, high up in the register of the workʼs opening bells. The piece ends in a gentle wash of complementary tonalities (tonal, whole-tone), with S–E–S continuing to sound in the center of it all, as well as ensconced in the now distant bells. The bell chords themselves come from the end of Les noces, and Stark notes that his last correspondence with Stucky included “us sharing our admiration for that ending.”

Three of the composers on tonightʼs program—Bartok, Lutosławski, and Stucky himself—openly acknowledged their debt to Debussy. His Syrinx, composed in 1913 (the year of Lutoławskiʼs birth), makes it clear why: with its masterful mixing of tonalities (the 3-note chromatic cells, pentatonic flourishes, and—saved for the very end—a simple descending whole-tone scale), it unfolds in what Stucky has called a “stream-of-consciousness narrative,” and presents a post-functional manner by which to organize harmonically viable forms, something all three composers exploited in their own music.

“Since an early age,” Stucky also harbored a love for the Spanish Songbook of Hugo Wolf, and in 2008 he arranged a set of eight of its songs for various singers with orchestra. His version of “Bedeckt mich mit Blumen” was dedicated to Rachel Calloway, who sings it tonight in Wolfʼs original version. For Rachel, this song “reflects Steveʼs love for his friends, music, life, and the world around him.” In the great romantic tradition, Wolf sustains an understated ecstasy by reserving for the final bars, after the singer has finished, the songʼs only cadence in the tonic.

The German lieder tradition suffuses Aus der Jugendzeit, into which Stucky weaves music by Schoenberg (Pierrot Lunaire) and Mahler (Das Lied von der Erde), creating what he calls “the fabric of yearning for a time and a musical language long past.” And though we tend to think of the German and French traditions as polar opposites, Stucky reminds us that, at least in the twentieth century, they are not so: he notes that Debussy had a copy of Pierrot Lunaire on his piano when he died, suggesting “it was one of the last scores he was studying.” Although fixated on the past, Aus der Jugendzeit was a piece for beginnings, too: it marked Stuckyʼs first collaboration with the Dolce Suono Ensemble and instigated a lasting artistic partnership with DSE and its founder Mimi Stillman, who performs it tonight.

Stucky has referred to his extant piano catalog, with characteristic humility, as “vanishingly small.” When he set to writing his Album Leaves, he wrote short pieces that each depend “on the clarity, pungency, and immediacy of a single, arresting sound-image.” He also leaned heavily on the two twentieth-century composers that reinvented the piano the most: Debussy and Bartok. Itʼs easy to hear how the perfumed arabesques of Debussyʼs Voiles and the biting, percussive dissonances of Bartokʼs Free Variations are each reflected and refracted in the selections fromAlbum Leaves paired with them tonight, as if Stucky is holding a private conversation with each, calling down the decades that separate them. As a centerpiece interrupting this glimpse into the composerʼs studio is the haunting and —incredibly, given its brevity—transfiguring Dirge by Bartok.

Lutosławskiʼs Grave for cello and piano was composed in memoriam the Polish musicologist and Debussy specialist Stefan Jarociński, and begins by quoting the first four notes of Pelléas et Mélisande. These opening four “white” notes are immediately contrasted with a handful of “black” notes, and the entire work, which Lutosławski crafts to provide “the illusion of a quickening tempo,” springs from this juxtaposition.

So, too, Stuckyʼs Dialoghi for solo cello. He begins with a set of six, rising “white” notes that spell “ELINOR” (Frey—the workʼs dedicatee), and immediately falls down through a soft fluttering of “black” notes. Both these elements—the name-theme and juxtaposition of “white” and “black” notes—permeate the seven variations that follow, and the work ends with a registerally (not literally) inverted restatement of the name-theme. The title Dialoghi is lovely in tonightʼs context, as we hear this piece beside Lutosławskiʼs Grave, but Stucky also stresses in his notes the “dialogues” that exist in friendship, in “conversations about books, music, paintings, films, psychology, religion, food, and all things Italian (hence the Italian title).”

The “white” notes that serve as the starting point for Lutosławskiʼs Grave and Stuckyʼs Dialoghi are spun into the principal sound world of Harold Meltzerʼs Two Songs from Silas Marner. Friendship is at the heart of these songs, too: Meltzer recalls that this was the first piece of his that Stucky heard, and he reached out to him, initiating a long friendship. Reflecting on George Eliotʼs tale tonight, Iʼm struck by the easy analogy between the solitary work of the composer and the miserly weaver, spinning out the stuff of his precious gold in solitude.

James Mathesonʼs “Clouds ripped open” features a restless piano part, with triads constantly morphing one into another, their borders blurred as in a rainbow. Ringing bells have been present in many of tonightʼs works, and they return here at the beginning of “Is my soul asleep?” Matheson (who studied with Stucky) describes Machadoʼs poems as “urgent, modern, and sometimes devastating in the sheer loneliness of their perspective,” but not without hope: the two stanzas of this last song are given lovely poetic tempi, first “Lost,” and then “Found; slower,” and the music aspires to eternity in its closing tintinnabulations.

It is astonishing to hear Stuckyʼs Sonata for Piano tonight in such close proximity to his Album Leaves. Though following it by a dozen years, the Sonata is his only subsequent foray into writing for solo piano, and any reservations Stucky had about writing for the piano seem to have been completely overcome. Stucky identifies the primary materials of the work: the opening “grim, gruff music” juxtaposed with “a tiny wisp of arioso melody,” and a repeating, “tolling bell.” From these he fashions a powerful, monumental structure, the centerpiece of which is an imposing chorale that literally takes over the work. Stucky describes the ending of the Sonata:

If one thought of a piece like this as a struggle between opposing musics—turbulent vs. lyrical vs. calm vs. light-hearted—then one might interpret the close as a somber outcome. But I prefer to think of it as what Wordsworth called “emotion recollected in tranquility.” The exuberant fast sections and the luminous chorale really are the twin hearts of the piece for me. Thus for me, despite the substantial quantity of dark music, the light carries the day.

The Sonata is dedicated, simply, “to my wife Kristen.”

In the days and now weeks since Steveʼs death there has been a constant stream of tributes and reminiscences online and in print. These remembrances—professional and personal—are a testament to the far-reaching impact he has had. Running through them all is a constant thread: Steveʼs humility, his graciousness, his willingness to help, advocate, and praise when he could. He was a great citizen of the American musical community, “a man,” his son Matthew has beautifully written, “of bottomless kindness and empathy,” and we are inestimably poorer without him. One canʼt help but wonder why these qualities of his, so universally praised and admired, are nonetheless so rare. Kristen Frey Stucky has poignantly urged us to “honor Steveʼs life by continuing to appreciate his music and the kindness that he conveyed to all.” Let us also honor him in this way: by going and doing likewise.

— Jeremy Gill

Squaring the Circle

I wasn’t with Mom when she died. My last time with her was about a week before her death. I had come from my home in North Carolina to Virginia for the weekend, as I had every weekend since my mother’s diagnosis of stage 4 brain cancer three months earlier.

It must have been a Sunday and therefore time to make the drive back, because I had my clarinets with me in the hospital room. Mom lay there dying, for all real purposes comatose – her brain function had slowed tremendously and her body had begun to shut down. All throughout that day the machines monitoring my mother’s condition continuously beeped and hummed, a monotonous and terrible metronome that kept ticking down the time as we all sat waiting for nothing. As the time came close for me to leave, one of Mom’s nurses noticed that I had brought my horns with me and asked if I would play something. Now, in a normal situation I would automatically decline that request. This was not a normal situation. After a moment of hesitation I put together one of my instruments, an A clarinet that my Mom had bought for me at the beginning of my professional career, and began to play from memory. I played the piece I and every clarinetist know the best, the Mozart clarinet concerto.

I played. It was quiet. I could hear the sound of my instrument bouncing and echoing down the hallway and into open doors. I listened as the floor quieted. Then: at first ever-so-slightly, then more and more obviously the beeps which had been keeping time so steadily all afternoon began to quicken. Several machines ramped up their activity – her heartrate began to rise, her brain activity picked up slightly but obviously, and she began to breathe just so slightly faster. I played as though suspended in time, the notes coming to my fingers without effort. This continued through the time I continued to play – it seemed like a half-hour, but I know the music is only about five or six minutes worth. Slowly again everything began to return to as it had been before I started playing, and then it was the same. During it all my mother never opened her eyes or made any other physical indication that she had heard me, but I believe she had. I think she had. It was the last time I saw her alive, and the last time I communicated with her in any way. I have some comfort at least that she knew I had been there.

Now, coming on four years later, I am a father of a one year old son named Saul. A few months before Saul was born, I got a new instrument to replace the one I had played for my mother. I still have the old one, but unfortunately clarinets have a shelf-life and this one had just run its course and then some – it was hard to let it go. Nonetheless, it’s always exciting to get a new horn and this was even more exciting, a new instrument made by hand just for me. I hurried home after getting the instrument. Right away I sat Rachel down, in theory for her to listen and give her opinion, but really just to tell me how great it sounded and soothe my buyer’s nerves. As I played, Rachel jumped in her chair. It was Saul in her belly, moving and kicking inside of her. As I played he continued to bounce and turn, his gestures reflecting the loudness or softness of what I was playing, until I finished.

I put my horn down. It was quiet. I stood there quietly too. It was distinct: in that moment I felt and, I think, understood the connection that had just been made. There was, for just a moment, a bridge between two people who would never meet each other: my unconscious mother and my not-yet-conscious boy. It was almost too much to feel – the end of one life and the beginning of another, connected through me in a way I immediately recognized. It is a thing I feel lucky to have experienced and a thing I will carry with me until I die myself. Maybe Saul will be there to play for me.

Open G Podcast #8.1: Steven Stucky

Here is a re-release of a Podcast Chris did last year with Steven Stucky. Sadly, Steve passed away on Sunday. We wish peace to his family and friends. Please enjoy this interview, originally released October 23, 2015.

Dealing with Disaster

There are moments in a performing artist's career that are truly terrifying. It is part of the essence of live performance that anything can happen - from sublime moments of absolute genius to complete and abject failures, all happening in real-time. When an audience is there to see you perform, and especially when they've paid for that experience, there aren't any real second chances. Oh, sure, every now and again you'll hear of a performance that gets off to a terrible start and everyone agrees to just begin again, but that's truly rare. For the most part, performances go roughly as expected - there are things you would like to have another shot at and such - bobbles, intervals you didn't quite make seamless. etc. - but usually you get to the end with no real harm, everyone claps, and it's on to the next one.

Sometimes disaster strikes.

In the past year or so, I had two moments of real disaster. Both were during the most important concerts of my life, and on both occasions I had to come back and play a show of equal importance the very next day. The first involved a memory slip and the second a technology problem and both needed to be overcome, or the next days' shows were going to be absolute hell. What happened and how did I deal with it? Well, let's get to it, shall we?

In November of 2014, I gave the world premiere of Jeremy Gill's "Notturno Concertante", a concerto for solo clarinet and large orchestra. There was a Saturday night show, and then a repeat performance Sunday afternoon. Jeremy and I did a podcast about this here - it's one of my favorites. Because I am an idiot, and an aggressive one at that, I decided that giving the premiere of a brand-new super-difficult 23-minute concerto from memory was truly prodigious, and so I went for it. I had a lot of time and a big memory, plus I would absolutely play Mozart or Nielsen from memory, so why not this? I drilled and drilled and drilled. I made a strict work schedule: a serious workout of a warmup in the morning, a long session working on the technical spots and smaller sections, and then one more session later which was all runs of longs sections (and, for the last month or so, the whole concerto) from memory. In fact, as soon as possible I was practicing without the music all the time, even for detailed technique work. I would say I spent the last two months without looking at the music. I had it cold.

Rehearsals with the orchestra went well, though I immediately decided that I would never ever try to memorize a concerto premiere again. It was almost unbearably intense. I thought the nerves would come from standing in front of an audience, but in fact it came from standing in front of the orchestra, in front of a hundred or so of my peers. They were totally cool, by the way. As any orchestra would, they approached a new piece and an unfamiliar soloist somewhat gingerly at first, but the piece is really great, and I'm not an asshole and clearly knew the piece in and out and was tagging the shit out of it, so we got along just fine. Still, I did not expect the level of pressure from myself to do well in front of my colleagues. It's hard to explain.

Saturday night comes. I'm ready. Dress rehearsal had gone well. Let's do this. I had to wait through the opener, Bernstein's Symphonic Dances from "West Side Story". Great stuff, only I'm not listening, really, besides noting where they were and how much time I had left. Got my focus on, repeating a mantra I've had for a while which slows me down and gets my head in the zone: "focused, and in control". I say it a few times to myself. Focused, and in control. I hear the Bernstein end, the applause. It's on.

I go out, and I'm sailing through. I have this thing where I don't remember details of my best performances - I mean, I know I was there, and I know what generally happened, but I won't be able to recall whole movements or any specific moments. I don't remember shit about the first half of the performance, so I think it was going well.

And then my memory failed.

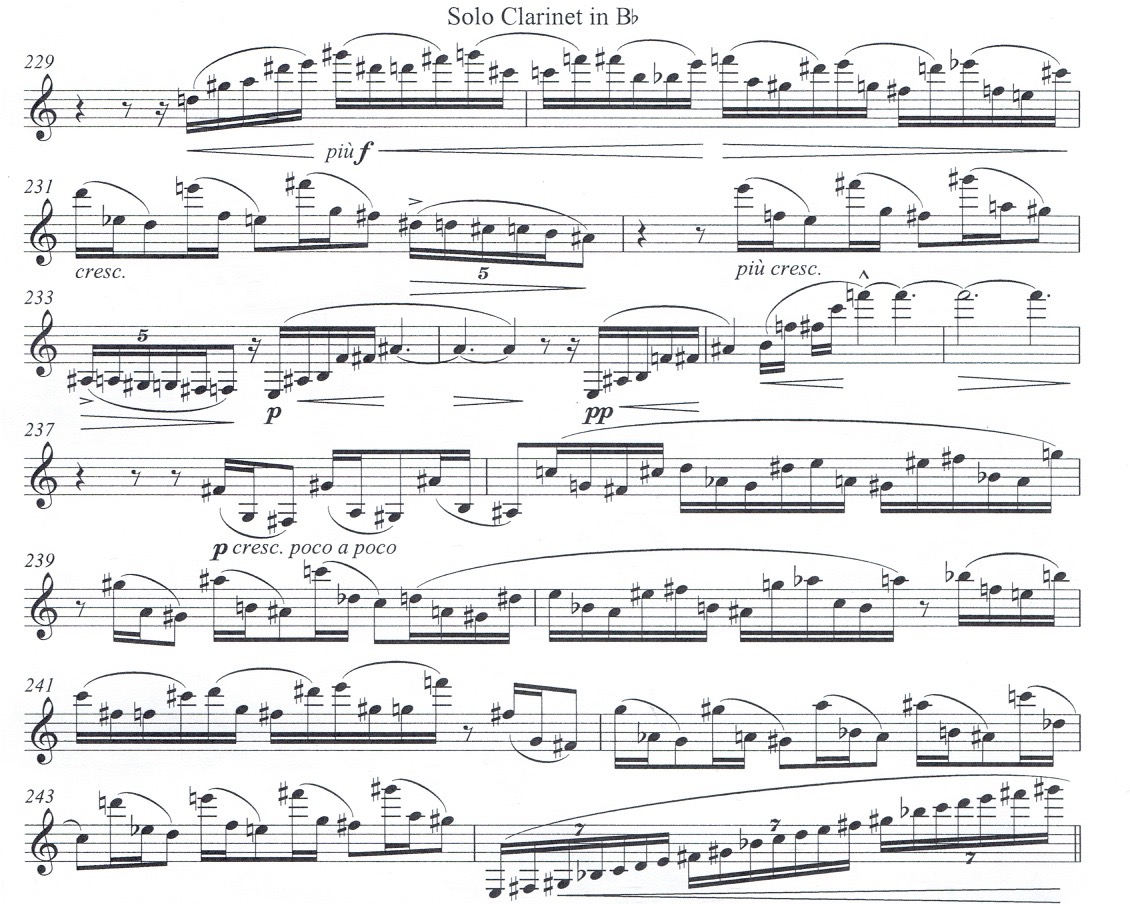

It was somewhere in here, a section in 9/8 which moves out at an insane 100 clicks on the metronome:

Bitch

My non-musician friends can probably look at that and generally tell that's an unfriendly section. My musician and clarinet friends can tell that it's even more unfriendly than you think, due to the chromatic AND wholetone stuff, plus a lot of going over the top break, and oh yeah it's fast.

Anyway, somewhere in there I fucked up.

I have no idea what happened. None. I do know that I found myself on stage with literally no idea where to put my next entrance or, after a second or two, what notes to play at all - it just happened so fast, and I was just there, going Oh My God. What do I do? I noodled. I know it was 10 to 15 seconds, tops, but it felt like fucking forever. I recall my thought process somewhat:

Oh shit.

Where am I?

I don't know.

What should I do?

I dunno, do something!

Ok, how about this?

That does not appear to be working. Try something else

How about this?

I don't know, maybe?

I knew the long whole tone run at the bottom was coming up. Does it end on a double high Bb? You bet your ass it does, and thank god for it. I decided the timing felt right and went for the whole tone run, knowing there was a big orchestra moment there, and if I was right we'd hit it and if not, I was going to hang on to that high Bb until they caught me. Lo and behold, I'd guessed right and thankfully I joined the orchestra correctly. Doubly thankfully, I only had about another 45 seconds of playing before a long break. Then I'd have a little while to recover, maybe as long as a couple of minutes. I made it, hanging on for dear life.

I still had 10 minutes left.

I caught my breath. I drank some water. And then I had to straighten myself out but quick. I had to forget it. One of the things I lean on heavily is sports psychology. High-level athletes deal with incredibly high levels of competition and pressure to succeed. What separates the great from the good is the head game, the ability to be mentally stronger and better-prepared than your opponent - or even yourself. In that moment, I thought, "Tiger Woods would forget this (I was obviously thinking of Tiger in his prime - an incredibly focused athlete). A great cornerback would forget this". Great athletes do completely whiff sometimes. But if you dwell on that whiff, another is sure to follow, and then another behind that, and then you're done. Tiger would occasionally shank a drive, Richard Sherman gets burned for touchdowns. It's bound to happen when you're doing difficult shit on a high level. What makes an athlete like Tiger in his prime special is the ability to truly leave mistakes behind. So, say Tiger borks a drive into the woods on the left. When he approaches that ball, it has become its own singular and particular problem. It no longer matters how the ball got there. It's there. How do you solve this problem that now presents itself? In the same vein, a cornerback or safety must let go of a great play or a blown coverage, because the opposition will assuredly test you again, and you'd best be ready.

So forget it. And I did. Played the rest, went fine. Took my applause, sat in the audience for the second half like a good boy, and got the fuck back to my hotel room.

I was devastated. I had spent so much time, and LOVE on this thing, and I couldn't believe I had dropped it like that. I called my wife, and I broke down and wept. I felt like I had let Jeremy down. I left like I'd let myself down. I had truly done everything I knew how to prepare for the moment, and I had dropped the ball. I couldn't believe it.

And I had to do it again tomorrow.

How? How should I prepare myself to overcome the memory slip and go out and tag it in my only other opportunity? Sports psychology had saved me in the moment, so I returned to it. The first person to enter my mind was Lebron James. Say what you will about him, but Lebron exists (and excels) on the highest plane of high level athletes. Yet he will miss more game-winning shots in his career than he will hit. He will occasionally have a 12 or so point playoff game, which for Lebron is throwing a big bag of bricks down a well. But an NBA player has an 82-game regular season, not to mention Lebron is usually playing in the finals, so add another 20-odd games onto that. That is a ridiculous number of times to have to get ready, be prepared, and have your head straight. So, I thought, what would Lebron do after a poor game in, say, game 2 of the NBA finals? He's going to have to come out well in game 3, especially with the opposition trying to seize an opportunity to take control of the series. I thought, he probably trusts his preparation. He probably trusts his routine. Everyone has an off night. Shooters keep shooting. That was it. Shooters keep shooting. The ball will go in. I thought, here's what you do. You forget about tonight. You get a good night's sleep. You get up, you get a good breakfast, you do your routine because you trust it, you check out the spot you failed on, but not too much: you actually know it, so just make sure the corners are swept out, and then just go do it. You know it. You didn't leave any work behind. Go do it.

And you know what? I did! I'm not going to say that no bricks were shat as the moment approached and then....PASSED! I definitely gave myself a big mental high-five, and the tiniest fist-pump on earth, and then got back to the business of finishing the piece off proper-like, which I did. It was a great success. Jeremy was happy. I was, for a moment, happy. More than anything, I was proud of my mental game for getting past the disaster of the previous night and delivering like I knew I could. I'm not sure I could have done that a few years ago.

Cut to this past October. I had two opening nights for Open G Records at National Sawdust, which, I'm proud to say, has become one of "the" places to play here in the city. It was a huge opportunity. I had two full variety shows of my favorite players, the guys on my label. All living American composers, some of whom were there including Mario Davidovsky, Steven Stucky, and my dear friend Ed Jacobs, who will become central to this story. Full lighting and amplification setup, two-time classical Grammy winning producer Adam Abeshouse running the live sound. I set up the concerts, I had four of my players from the label in town for the show, plus I played during the shows as well as emceed the entire evenings from a microphone at the side of the stage. In short, a big deal.

The setup for the show. I mean, LOOK at this place!

One of the pieces I played was by the aforementioned Ed Jacobs - a piece he'd written for me called Aural History, which I had premiered and recorded, and was very excited to give the New York premiere of. This is it here, with me and my boy Xak:

So, the piece has a lot of pages, which I often spread across a few stands. In this case, we were making a film of the concert, so in order to present a cleaner look for video, I transferred the piece onto an iPad with a page turning app, which I connected to a bluetooth pedal.

This one right here. NOTICE ANYTHING?

I had gotten the pedal some time before the show in order to get used to it, and it did take some getting used to. It's a pretty simple idea though, right pedal turns forward, left turns back. You could read a book this way if you wanted to. After a while it became second nature, plus it worked like a dream. I was a total convert.

Cut to the middle of the first show. It's going great. It's a long, super crazy day, especially to be in charge of, but it's really going. I play Reich's New York Counterpoint, which I'd just recorded with Adam Abeshouse, we have the New York Premiere of Stucky's violin/piano sonata, I do a bit with my friend Jason, and then it's time to play Eddie's piece. It's a hard piece, but I really love it, and I'm pretty sure that I've spent more time overall on it than any other piece in my lifetime. Xak and I had recorded the piece and know it well and we're both ready to go, especially after I hit the gas pedal hard and really rocket us into the start of it.

It's pacing along really well - Ed marks the beginning "on the edge", and I think we're really living on that edge. That's where I want it to be, and I had put in another level of work on the piece to make it so. First page turn comes, no problem. Kick some more ass, looking to rain down fire in the 3rd page. I have three measures of rest at the bottom of page two. I hit the pedal.

Nothing.

I hit it again. Nothing. Oh, man, this is real trouble. Still, you can turn the page with your finger. I do so during the rest. There is no rest on the bottom of page 3.

What. Do. I. Do. Now?

I play, trying to not lose focus whilst navigating a briar patch of notes and gestures, much of which happens in unison with the piano - not exactly a good time to collect my thoughts, much less formulate a plan. I'm just hoping the pedal had a hiccup and it'll be no harm, no foul and let's get to the end. Here comes the bottom of page three, and...

Nothing.

Xak goes on. He has to. That's what the piece does, it goes on. But I'm hopelessly fucked now, because I've had to take a couple of seconds to swipe the page (to my recollection it took two tries) and then get my hands back on my horn, and then where the fuck am I? I know I'm on the top of page four out of five pages of continuous 16th and 32nd notes. Other than that, you got me. I have to stop Xak. "Let's just go at the top of that section", I say. A quick look confirms my knowledge that there is a two-measure rest at the bottom, and I'll be able to finish this movement without another incident. I know I will not be so lucky for the next two. I finish the movement.

Fuck. I have to figure this out (or not) right now in front of an audience. What can I do? This is happening right now whether I like it or not. I'm a little fortunate in that I'm generally a funny guy who can at least be somewhat witty when the chips are down. The chips are down. I'm not sure what I say, but I say something like, "hey, sorry folks. Excuse me for a second while I check out a technical issue I'm having". And then I pick up the pedal. Seems fine. I press the pedal down with my finger. Nothing. I try the page back. Works fine. Try the forward again. Nothing. Wiggle it a little bit. Nothing. I put it to my mouth and blow on it, which is a call-back to part of the bit I had done earlier with Jason (clarinet players are always blowing shit out of their horns in rehearsals and performances - it's kind of our calling card). Secretly, I'm hoping it actually works. It doesn't. OK. So now I've spent about a minute doing this and that's about all I can afford, especially as I can't seem to even start troubleshooting the issue. I have to go on.

I go on. Second movement is slow. I still have a page turn. I deal with it as best I can. I know the third movement is fast, at least two fast page turns. Fuck. I stumble through them, the last coming before maybe 20 last seconds of music, all of which is pure hell, just one of those times where you know you aren't on but there's not a damned thing you can do about it, so have a big bite of that shit sandwich for the road.

Pretty much like this

It's done. Xak and I take the applause, I point to Ed so he can get some applause. I walk over to the microphone to introduce my friend Scott, who's getting ready to play some Boulez; and also to vamp a little bit while the crew moved the piano offstage and did some resetting in the hall. So, now I have to spend four or five minutes chatting with these folks when really, truly I'd rather be in the green room throwing up. My instincts say to address the problem, but I have no idea what I'm going to say. I just start talking. I say something like, "hey, everyone, thank you. So, I had a little technical SNAFU there, I'm sure you noticed. Trying something new with new technology, sometimes that happens." Then I smile a bit and say, "if you'd like to hear a COMPLETE performance of that piece, you can hear it on my CD, available for sale in the lobby!".

I'm gonna switch back to past tense now, ok? So I finished my spiel about Scott: best friends forever, great player, good dude, yadayada. I was trying my best not to really look at Eddie - it was too hard. I caught a glance or two. There he was, all supportive looking and smiling. That made it worse.

Even after I finished speaking, I STILL had to stay out in the hall, because I was assisting Adam with the quite extensive technical part with the Boulez that Scott was playing. No hiding for me; not one moment yet offstage to even sigh. I sat there, trying to focus intently on the music, trying to be at my best for Adam and Scott (and Boulez). I did my best, I really did, and it was fine. But humming behind my eyes was a brewing sadness. Of all the pieces to have a problem, the last one I wanted was for it to be Ed's. See, Eddie is special to me. When I showed up at East Carolina as an interim professor in August of 2001 (I'd get the job outright the following year) Eddie was the first person to try to connect with me - in fact, he took me to dinner my very first day on campus. I latched on to that, and we became fast friends. We played poker, we lunched several times a week, we got high and listened to Radiohead (sorry, Eddie, hope that don't cause problems for you, but you're a full professor - fuck em), he shepherded me through the ends of a couple of disastrous relationships. Real friends. And we made music together, the cornerstone of which was the piece that had just eaten some shit on its New York premiere. Damn. Damn damn damn. As I sat through the twenty-odd minutes of the Boulez, I sank further and further into a plush couch made of melancholy. I knew it wasn't truly my fault, but it had happened. I had let Eddie down. I have an interesting artifact from that moment. As I mentioned, we were making a film of all of this, and the crew had placed a small camera on Adam's desk.

I know I'm probably not showing what I was feeling. I can look at myself, though, and really feel it. Damn.

So, the concert finished. Had to shake hands, meet and greet, do the thing, be the guy. Stayed at the front because Ed was in the back. Eventually I made my way back there. He was talking to a couple of people I knew had shown up just to hear his piece. Damn. I shook his hand, told him I was sorry. He was cool and totally supportive, as I knew he would have been even if it HAD been totally my fault. It didn't make me feel any better. I knew it had to be a disappointment, even if he wasn't really going to show me. I tried to believe everyone when they said I dealt with it with elegance and humor. I guess I did, but again, it didn't make me feel any better. To this day I have trouble dealing with it. Eddie and I normally speak or text quite regularly - maybe every couple of days, at least weekly. Since the concert I have basically ghosted the shit out of him. It's hard for me to get over. I feel the disappointment still.

I shook more hands, I went to the bar, I got all my guys into a car back to Manhattan, and then I Googled the living fuck out of the pedal issue until about 2:00 in the morning. It was working again. What the hell? I decided that it was a bluetooth pairing issue, and that it had tried to randomly pair with someone phone and somehow screwed my connection. See, here's the problem: I had to come back the next day and play another show. I had planned to use the pedal because the piece I was playing (Davidovsky - Synchronism 12) stretches across five stands when using paper (it's not some odd format or anything, it's just that it's 14 pages over six minutes, and no time to turn pages - you just have to kind of lay them all out in a row). Again, that looks like shit on video. I fixed the problem with the pedal. I tried it over and over. 100% success rate. I went to bed. I woke up. I tried it a few more times. 100%. OK, the bluetooth was the problem. I'd just add a part to my talk where I ask everyone to turn off the bluetooth on their phones, boom. Problem solved.

Cut to 5:00. Show's at 7. It's been another crazy long day. I only have time to run through the Davidovksy, because we've spent all day getting good takes of Boulez with Scott. It's important, the run-through, because the Davidovsky has electronics and there are always issues of balance, etc. Check the pedal again. No problem. Sweet. Start the rehearsal, it's going fine. I go for the first page turn.

Nothing.

I lose it. I really lose it. Not AT anyone. Not TO anyone. But the emotions of the last couple of days, not to mention the months of planning that had gone into the damned thing, erupt out of me in the form of a lengthy, deeply blue, and oddly specific FUCK YOU to the gods, to the universe, to anything you might have on hand. Even on everyday occasions, I can swear with the best of them. Now I really pop the top off, like a barrel full of illegal fireworks. I have to get out of there for a second. I go out onto the street. A late October wisp of a mist is in the air, and it feels good. I take a few deep breaths, walk up and down the block. I gotta figure this out. I call my wife, tell her to bring my sheet music. I walk back in.

While I've been gone, the crew has figured out a jury-rigged solution to the problem: the left, or "page back" pedal, has always worked. They disconnect the cable from the right pedal, extend it a bit, and run it to the left. It works like a charm. That's the solution (and the source of the big "X" in gaffer tape on the photo at the top of the page) Should I trust it? I did mention before that I'm an idiot, right? Meanwhile it's 6:15 and Davidovsky has arrived and he'd like to hear the piece, because of course he would. Well, here's a chance for at least a real-world test. I play it, everything works fine. I'm rightly nervous about the tech, and it shows a little, but basically everything works. He tells me to play softer in spots. Cool. He doesn't know there was a problem. What problem? Time for the show.

Show starts and it's going well. It's becoming apparent, actually, that it's going REALLY well. It's like the stress and effort of the past couple of days fall away and we all say "fuck it" and just go out and play, and that's when the good stuff usually happens. The time approaches for Davidovsky. I wait backstage, clutching my horn and my pedal. Please work. One time.

I go out, make an intro at the mic, and then walk to center stage to do the thing. I start by myself. The electronics enter. The first page turn comes really fast. I cross my fingers (figuratively, obv) and hit the pedal with my foot.

yes

Oops. I make a mistake because the fucking thing actually works! Can't do that. I turn my focus to executing the piece, and everything turns out well. Everyone seems happy with it. I am relieved. I hit the mic again, introduce Scott, and sit down to assist with Adam. As I do, I see Eddie in the audience. He comes to both nights even though his piece is one on the first, because he's a mensch. I put a big smear of regret across my relief. Still, the concert finishes well and is an actual good time (I know, at a classical show! Shock!)

Cut to now. I return to speaking in past tense. So that's what happened. Two instances where I had to deal with truly difficult issues pretty much in real-time. The first key to overcoming things like that is preparation. Without hard, dedicated preparation you can never really get to the second key, which is trusting yourself. Without those two things, you can't achieve the end, which is to be able to forget mistakes or problems and be the best player and person you can. As I mentioned earlier, I'm not sure I could have gotten past those things so quickly when I was younger. I find that it's a skill like any other, and gets better with practice. Be prepared, leave mistakes behind, and be better in every moment moving forward.

I'm going to finish this one with a thought that's so good I wish it was mine. It's actually from Adam Neiman, who is a fabulous and wise pianist. As part of his preparation, he does as many full runs of pieces (that is to say, he starts at the beginning and plays all the way to the end without stopping) as possible. For some pieces, including concertos that run 30 to 45 minutes, his full-run repetitions number in the thousands. Pianists. . .Anyway, that is (almost literally) insanely prodigious. So I asked him about why he goes for that level of prep. He said (and I'm paraphrasing - it's been a few years), "well, everyone gets to that spot in a performance where you go 'oh, shit. What's next?'. The thing is to have the answer to that question".

The thing is to have the answer to that question.

And, Eddie, I'm not done with our piece in New York. Not by a damned sight. It's the next thing to overcome.

An asshole comes to all of my shows

Open G Podcast #8: Steven Stucky

In this podcast, Chris talks with 2005 Pulitzer Prize winning composer Steven Stucky about music, his process, and much more